Why Do We Celebrate Labor Day?

By Sarah Clendenon • September 3, 2023Happy Labor Day to you, Idaho Dispatch readers! Why do we celebrate Labor Day?

Working conditions were very harsh in the United States in the late 1800s. Americans were employed in factories, fields, shops, railroads, and mines often for 12 or more hours per day, six days per week. Children too. Those who were indoors worked in cramped, poorly ventilated spaces. It was common to be punished if you spoke or sang while you worked. So, for 12 hours per day the people and their children worked in silence, in what one can only imagine must have been smelly, sweaty, and debilitating circumstances.

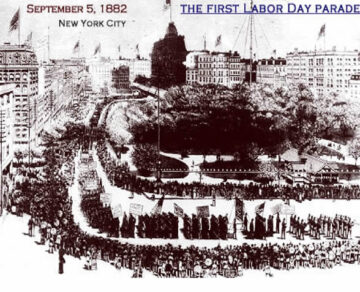

Protests, rallies, and strikes began springing up as the idea spread for workers to demand better work conditions. On September 5, 1882, the union leaders of New York organized what is widely accepted as the first Labor Day parade. Workers took to the streets to march together in defiance of the poor work environments and expectations. After the march, the people held rallies and spoke, picnicked, danced, and set off fireworks to celebrate their day of gathering and unifying their voices. It is said that tens of thousands of people participated that day.

Photo from US Dept of Labor

Unfortunately, the first Labor Day parade and celebration did not convince employers to improve the workplace misery. Years of continuing harsh conditions went on until the Haymarket Riot in May of 1886. Thousands of people demonstrated in the streets of Chicago, demanding employers limit workdays to eight hours. The protest lasted for several days. A bomb was detonated during the incident, killing 15 people. Seven of the 15 were police officers, which many people claim created a new level of discordant tension between police and civilians.

The Haymarket Riot inspired workers in France to gather a few years later, at which they declared May 1st as May Day, another holiday to celebrate workers. May Day‘s name was changed to International Workers’ Day and is still celebrated in many countries.

Protests continued, especially in the railroad industry. From this source,

“[In] May 1894, workers went on strike to protest 16-hour workdays and low wages at the Pullman Palace Car Company, which manufactured railroad cars in a plant near Chicago.

AdvertisementMembers of the powerful American Railway Union (ARU) joined in, refusing to move Pullman cars. Rail traffic across the country was crippled.”

The Pullman-ARU strike motivated President Grover Cleveland to finally sign the bill officially recognizing Labor Day as a national holiday in 1894. Because the strike disabled the railroad industry so drastically, Cleveland also ordered military to end the boycott in Chicago. Angry workers became a rioting mob, and the clash became deadly. National guard fired rounds into the crowd killing several dozen people.

According to the same source cited above, after these large influential events, it was common for the leaders of the workers’ movement to be persecuted. After the Haymarket Riot,

“Eight men labeled as anarchists were convicted in a trial in which no evidence was presented linking the defendants to the bombing. Seven of the men were sentenced to death and four of them were hanged.

They were among many people unjustly tried and executed in efforts to tamp down the growing labor movement and rid it of radical leaders.”

23 or 24 states (there are conflicting reports) celebrated Labor Day before it was declared a national holiday in 1894. From the webpage for the US Department of Labor,

“Before it was a federal holiday, Labor Day was recognized by labor activists and individual states. After municipal ordinances were passed in 1885 and 1886, a movement developed to secure state legislation. New York was the first state to introduce a bill, but Oregon was the first to pass a law recognizing Labor Day, on February 21, 1887. During 1887, four more states – Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York – passed laws creating a Labor Day holiday. By the end of the decade Connecticut, Nebraska and Pennsylvania had followed suit. By 1894, 23 more states had adopted the holiday, and on June 28, 1894, Congress passed an act making the first Monday in September of each year a legal holiday.”

The day it was celebrated differed among those states. From the History, Arts, and Archives page of the US House of Representatives,

“…according to the Washington Post, the celebration alternated between the first day of September, the first Monday of September, and the first Saturday of September depending on the location.”

Over the years, despite the punishment of movement leaders, the pressure to improve workplace conditions continued, and began having an impact and effecting change.

“In 1914, Henry Ford more than doubled wages to $5 a day. When his profits doubled in two years, rivals realized he might be onto something. In 1926, he cut workers’ hours per day from nine to eight.

During the New Deal, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act limited child labor, set a minimum wage, and mandated a shorter workweek, with overtime pay for longer shifts. By the 1940s, the average workweek had fallen to five eight-hour days.”

Since 1894 when Labor Day was officially recognized nationally, it has been honored across the country every year on the first Monday in September.

Photo of the Women’s Auxiliary Typographical Union from US Dept of Labor

Photo from the US Dept of Labor

Feature image courtesy of the Library of Congress webpage, which captioned the photo:

“Today the country pays tribute to labor.” September 2, 1901. Deseret Evening News (Great Salt Lake City, UT), Image 1. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers

Tags: 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, American Railway Union, ARU, Chicago, Grover Cleveland, Haymarket Riot, Henry Ford, History, International Workers' Day, Labor Day, Labor Unions, May Day, National Guard, New York, Persecution, Protests, Pullman Palace Car Company, Railroad Industry, Rallies, Women's Auxiliary Typographical Union

5 thoughts on “Why Do We Celebrate Labor Day?”

Comments are closed.

I’ll be working today…usually do, so absolutely it’s a “labor day” for me. Thankful that I can physically do so…God is good, all the time. 🙂

Many professions, including Dairy, Farming and Ranching, remain 7 days per week, with no holiday’s.

It seems every Labor Day, I am hard at labor at home, even if not at my job. The example set by Henry Ford showed that industry can succeed and be profitable without taking advantage of workers.

So just a little more context, but many of the people working long hours did so because of the opportunities they had here in America which weren’t available to them in their native lands. And many others left and went back.

It’s always easier to judge from our time and our traditions than those of the time period in question…

It’s not all been a bed of roses in this labor situation. It was good for what it did in the beginning, but gradually it became a cudgel against any large business to further reduce working hours and increase benefits. Your article fails to include the Marxist push to incorporate the “workers” into their push for communistic control even in the early years of the movement. To whit, May Day (May 1st) was chosen in Marxist countries to celebrate the “workers”. One only has to look at the managerial hierarchy of labor unions in this country to see who REALLY enjoys the monetary benefits of these organized crime groups (think AFL-CIO) and it’s NOT the working class, especially when they forced their members to pay union dues or be ostracized.